On Snooker

It is a Sunday evening in early December 2014 in the northern English city of York. In front of a rapt audience and several million TV viewers, two men are playing the deciding frame of the final of the annual UK Snooker Championship (the second of three snooker 'majors'). The winner will receive £150,000 in addition to the title of UK Champion.

It has already been an incredible match. The favourite is snooker's number one draw, 39-year-old Ronnie The Rocket O'Sullivan, a prodigious and mercurial talent who, amazingly, first won the UK Championship aged 17 way back in 1993. O'Sullivan, from Essex, got his nickname due to his rapid and flamboyant playing style, which offered a stark contrast to the more deliberate approach employed by most of his contemporaries. Considered by many to be the most talented player in history, he holds endless snooker records and has career earnings approaching 8 figures.

O'Sullivan's opponent is Judd Trump, from the port city of Bristol, who already at 25 is a previous UK Championship winner and former world number 1. Despite this success, his true potential is as yet uncertain: he has so far failed to win any other major tournaments.

Ronnie O'Sullivan (left) and Judd Trump, before the match. Judging by their expressions (and indeed, according to the rules), there can be only one winner.

Ronnie O'Sullivan (left) and Judd Trump, before the match. Judging by their expressions (and indeed, according to the rules), there can be only one winner.

The previous day, O'Sullivan had got off to a fantastic start in the match, rattling off five of the first six frames by capitalizing on the mistakes made by his young opponent. From the very first shot Trump had been unable to relax, and every error seemed to increase his discomfort. O'Sullivan himself is a temperamental character, and this has often leaked through into his snooker, to the extent that a few years ago it seemed that he was on his way out of the professional game, having failed to win a tournament for several years. But recently he's changed his approach, cutting back on the number of tournaments he enters (dramatically reducing the amount of traveling and nights spent in hotels) and hiring a psychologist. This seems to have turned things around; he has both his game and his old swagger back, an intimidating combination.

For much of the match, it seemed like this psychological edge would determine the result. The match score rapidly became 9-4 in the first-to-10 contest, with neither player hitting full stride, and so seemed certain to end in anticlimax with O'Sullivan requiring only one of the last six frames. But then, seemingly relieved of the pressure he'd been under, Trump suddenly started playing extremely well. In sharp contrast to his play earlier in the match, his unforced errors vanished. He started winning frames in a single visit: where earlier in the contest he had been making 40-breaks, he was now making comfortable centuries. Trump took a scrappy fourteenth frame, followed by the next three frames with stunning breaks of 120, 127 and 86, making the score 9-8. O'Sullivan seemed finished, no longer able to make shots he'd had no trouble with earlier in the match. What was going on?

Trump, no longer having any expectation of winning, had begun playing in the fluent, carefree manner of a practice session. O'Sullivan had no response to this, seemingly unable to get over the winning line. This was compounded by a jogging accident he'd succumbed to, just a few days before his first round match, when he'd fractured his ankle. The physical strain was obvious; normally a twitchy bundle of nervous energy, O'Sullivan was reduced to hobbling around the table, grimacing in pain. Commentators and viewers alike were wondering whether he'd finally exhausted his mental reserves. Once again, snooker was demonstrating its psychologically unforgiving nature.

In common with other sports, and particularly non-athletic sports like darts and golf, the mental side of snooker has tremendous bearing on the outcome of a game played between highly skilled individuals. But there's another aspect of snooker which makes it even crueller. In golf, players alternate strokes. In darts (which I'll discuss another time), each player alternates turns every three darts. In snooker, if a player has a great opportunity to win a frame but makes a silly mistake, he must sit down while his opponent takes his turn. He is now powerless to prevent his adversary from potting all the remaining balls and winning the frame, added to which he'll have plenty of time to reflect on his mistake and think about the what might have been. Too much of this kind of thing can, and regularly does, break a player's spirit.

Before we continue, let's pause to examine what snooker is all about, for those of you who aren't quite sure. I’m assuming that you are at least casually familiar with the game of pool; here I will just describe the main differences between pool and snooker.

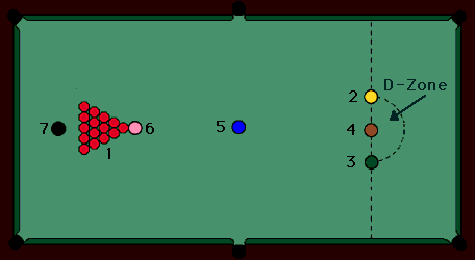

Snooker, in its professional form at least, is played on a very large table (roughly 12 feet x 6 feet), a fact not brought home to a typical pool player until their first foray into a snooker hall. The pockets are also much smaller than those found on a typical pool table. In addition to the cue ball (white), there are 15 red balls and one each of six other balls, known collectively as colours and set up as shown in the figure below.

The initial positions and values of the snooker balls at the start of each frame. Whenever the white ball is placed on the table, it must be struck from the ‘D’. While any reds remain, the colours will be respotted after being potted.

The initial positions and values of the snooker balls at the start of each frame. Whenever the white ball is placed on the table, it must be struck from the ‘D’. While any reds remain, the colours will be respotted after being potted.

The objective is to score as many points as possible, and this is accomplished by making a continuous sequence of pots (known as a break) of a red followed by a colour until all the reds have been potted. When a colour is potted, the referee places it back on the table on its designated spot, once again available to be potted following a pot of the next red. Once all the reds have been potted, the colours are potted in order of value (and are no longer respotted). The reds are worth 1 point each, while the value of the colours ranges from 2 for the yellow to 7 for the black. Therefore a maximum break consists of a clearance of 15 reds each with blacks followed by all the colours, for a total of 147 points. This is very rare on television; earlier in the tournament O’Sullivan had extended his world record by making his thirteenth televised maximum break (spanning a career of over two decades). Notoriously, during one of his earlier 147 breaks, O'Sullivan had held up proceedings for several minutes after potting just one red and one black, by asking the referee if there was a special cash bonus for getting a maximum. After being informed that there was not, he seemed intent on leaving the final black on the table with his score on 140. The referee pleaded with him to pot it, which he did by hammering the ball as hard as possible into the corner pocket. Even making a competitive century break (100 or more points in one visit) is a worthy accomplishment; a top pro will make a few dozen per season.

Ideally, a player will score enough points during a break that their opponent will concede the frame (individual game). For example, if you make a break of 70 points and your opponent is on zero with only four reds left on the table, he can only score at most 59 points by potting the remaining reds with blacks and clearing the colours. In this case, your opponent could continue by trying to make snookers, i.e., playing his shot in such a way that he does not pot a red and the white ball ends up close behind a colour, leaving no direct path to any of the reds. If a player fails to hit the correct object ball, a foul is called, and the opponent scores at least 4 penalty points. In this way, a player who requires snookers can still win the frame. Although it's considered bad etiquette not to resign the frame if more than about three snookers are required, with only one or two snookers required, a player will often play on.

In addition to break-building, a frame of snooker will often turn into a safety battle, with each player attempting to leave their opponent in as difficult a position as possible. This occurs when there is no easy opening red or when a player runs out of position during a break. Not having a viable pot, in this case he will attempt to snooker his opponent (or at least leave no easy pot), hopefully inducing a mistake that leaves him with an easy potting opportunity.

Most snooker tournaments are of a seeded knockout format, with each round played over a series of several consecutive frames. The UK Championship is best-of-11 in every round bar the final, which is best-of-19.

As with any skill, becoming an accomplished snooker player takes a huge amount of practice and a great deal of natural ability. This obviously requires access to a snooker table, which in the UK are mostly found in specialist snooker clubs. These generally consist of a large room containing one or two rows of snooker tables, no windows, at least one bar, and a clientele of highly variable moral character.

A snooker club. Most of these people should be in school.

A snooker club. Most of these people should be in school.

Once you've got access to a snooker table, have bought yourself a cue and have found a way to sneak out of school undetected, there's only two main problems to solve to become a good player: potting and cue-ball control. Potting has two components, namely getting the cue ball to go where your eye is looking, and getting your eye to look in the right place. Cue-ball control is based on the strength at which a shot is played and the point on the cue ball that the cue strikes. Striking the cue ball off-centre will affect the speed and angle at which the cue ball travels following contact with the object ball. For example, pool players will be familiar with imparting backspin by striking the cue ball below center, and side-spin and topspin are also employed frequently to get the cue ball to finish where a player wants it, making the next shot as straightforward as possible. All that stands between you and these simple goals is first-rate hand-eye coordination and a unflagging determination to execute thousands of hours of directed practice. That's the tough part.

Back in the old days, snooker was very much the preserve of the upper class. It developed from the game of English Billiards, which is played with a single red ball and a separate cue ball for each player. In billiards, points can be scored in several ways: by potting either the red or the opponent's cue ball; by getting your own cue ball to go in-off one of the other two balls; or by making a cannon (striking your cue ball so that it hits both the other balls in turn, from a single shot). Billiards was popular in the nineteenth century with colonial types, as a gentle method of relaxation in between hot and dusty forays aimed at civilizing the natives of the lucky country in which they were stationed.

As skill at the game increased, billiards was effectively 'solved'. Players would gradually manipulate the two object balls so that they were wedged into a corner of the table, and score endless cannons over multi-hour sessions, amassing breaks of thousands of points and boring their opponent into submission.

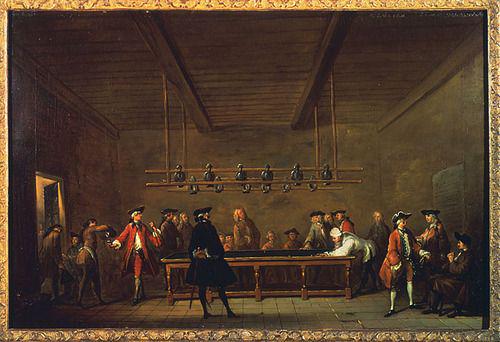

A couple of chaps playing billiards. As several of the onlookers are still standing up, this particular game is presumably in its first morning.

A couple of chaps playing billiards. As several of the onlookers are still standing up, this particular game is presumably in its first morning.

Clearly, a new and greater challenge was required. Snooker developed by gradual modification and extension of the rules of billiards. Initially limited to high-ranking British Army officers in India, it eventually spread to private clubs back home in England. Although it became quite popular in the interwar years, it didn't really take off until later, when it began to be televised on the revolutionary new colour television sets. As it gained in popularity, snooker clubs began opening up all over the country, and snooker itself developed a reputation as a working-man's game.

Thanks to television, by the late 1970s what few professional players the game could support became well known to the public, and the World Championship was regularly broadcast on the BBC. Then, in the '80s, the popularity of snooker exploded. There was even a top 10 hit record about the game. At this time, there was a variety of different characters playing snooker. As their main income derived from touring clubs and playing exhibition matches in front of small crowds, most of the players of this era were concerned primarily with entertaining the audience. They had neither the time nor inclination to spend hours practicing. These players were sitting ducks for the king of '80s snooker, Steve 'Interesting' Davis, whose unsmiling and relentless focus earned him massive wealth (and the ironic nickname). Davis won six World Championships in the '80s, and was the player everyone else wanted to avoid.

Snooker's popularity peaked in 1985, when little-fancied Irishman Dennis Taylor inflicted a rare defeat on Davis, 18-17, with the final black of the final frame deciding the winner of the World Championship. This concluding frame took over one hour, finished after midnight, and was watched by around one third of the British population, who couldn't take their eyes off the contest. Taylor had been 8-0 down: seemingly a broken man, heading for humiliation. Somehow he got the score back to 11-11 and eventually found himself 17-15 behind and needing all of the last three frames. He managed to win the next two to take the match to a decider. The final frame was riddled with errors, with some truly terrible shots played by both players. For once Davis was the one whose nerve (or perhaps stamina) failed him, missing a relatively simple black which would have won him the tournament. This climactic finale captured the public's imagination; snooker was now ascendant.

Dennis Taylor: he told ya he'd win (his glasses were investigated by sceptical officials, but ultimately deemed legal).

Dennis Taylor: he told ya he'd win (his glasses were investigated by sceptical officials, but ultimately deemed legal).

But the good times couldn't last forever. Despite this setback for Davis, the pattern was clear: bring to the game a thoroughly professional approach and you could make a fortune. This was reflected in the next batch of top players to come through in the '90s, first amongst whom was Stephen Hendry, who won 7 World Championships in that decade. The massive increases in prize money (the 1980 World Champion took home £15,000; Taylor won £60,000 in 1985; last year's winner got £300,000) attracted large numbers of youngsters who never needed to rely on the exhibition circuit to make a living. They were solely focused on winning, and had little regard for entertaining. The abundance of highly skilled but dull players must surely have contributed to the slump in popularity of snooker during the '90s and '00s; watching emotionless snooker-playing robots is emphatically not entertainment for any but the most ardent of fans.

It was against this background of seemingly terminal decline that Ronnie O'Sullivan made his breakthrough. A volatile character, in those early years he was as likely to crash out in the first round of a tournament as he was to win it (and often angrily threatened to quit the game in either case). Obviously incredibly gifted and playing in an easy, carefree style, he rapidly gained a large and vocal following. His behind-the-scenes antics and boisterous personality regularly attracted as much attention as his snooker. All this contrasted with most of the other elite players, adding an extra dimension to the game. He made his first televised maximum 147 break in 5 minutes 20 seconds, less than 9 seconds per pot (the first 147 at the World Championship1 was made by the Canadian player Cliff Thorburn in 1982. It took 15 minutes 25 seconds).

Although O'Sullivan remained a big draw, the disappearance of tobacco advertising post-millennium was another blow to snooker, ending the days of easy money. This was partially mitigated in 2007 with the deregulation of gambling advertising, and indeed bookmakers and online casinos are now prominent among event sponsors. Most recently, cockney chancer Barry Hearn gained control of the sport in 2010, and immediately made some big changes in an attempt to revitalize the game (shorter match formats, more tournaments in more countries around the world). Prize money is now increasing once again, and players from several countries are rising into the top ranking spots. Some of them even have personalities. In fact, it's fair to say that the game is now enjoying a mini-renaissance.

So why can snooker, at its best, be so captivating? Notwithstanding the delights of applied geometry, it's the psychological side of the game that's most enthralling. The ebb and flow of a match as the initiative is passed back and forth between the players. The emotions on each of the players' faces: determination as a break is painstakingly built; the crestfallen look following a bad miss; the exaltation of a century break; the frustration of running out of position just a single pot before a frame is won; hope giving way to despair as a player, sitting alone in his chair, watches his opponent clear the table. It helps to have played the game yourself, so you can appreciate the enormous skill, concentration and sheer willpower that's required to win at the highest level. It helps if you have some understanding of the volume of behind-the-scenes work that's required to reach the top level. It helps to be able to appreciate a master of their chosen craft performing at the peak of their ability.

Ultimately, the difference between a great player and a very good one is all in the mind. Some have the requisite steel; some don't. And with some, like Trump, it is as yet unknown whether they possess it – another facet that adds to the game's appeal.

So, back in the York Barbican Centre (merely a chalk's throw from the historic city walls), it's 9-8 to O'Sullivan, who still needs just one more frame to win the championship, but looks spent. Despite this, it seems like he's about to fall over the finish line as he quickly goes 59 points ahead. Just a couple of pots away from victory, he runs out of position and once again, incredibly, Trump punishes him by cooly clearing the remaining balls to win the frame 67-59. So it's now 9-9: a very unlikely comeback has been completed, and Trump, having won five frames in a row, is now one away from taking the title.

The final frame was as tense as expected. Both players made small opening breaks, after which the frame turned into an edgy safety battle. For many visits, neither player had a decent potting opportunity, and the back-and-forth tactical battle continued. If this was a Hollywood movie script, Trump would have somehow made a tremendous pot and narrowly won. But it wasn't, and he didn't 1 . Instead, perhaps feeling the pressure once again now that victory was within his grasp, he was the first to crack in the tournament's final safety exchange. He ended up letting O'Sullivan in, who made a 50-break to take the title.

Don't be confused Ronnie. You've just won the UK Championship, and everyone's applauding and there's confetti and a nice trophy and a huge cheque!

Don't be confused Ronnie. You've just won the UK Championship, and everyone's applauding and there's confetti and a nice trophy and a huge cheque!

O'Sullivan's reaction was mostly one of relief. Understandably, both players looked utterly drained. For Trump it was another narrow defeat. For O'Sullivan it was his fifth UK Championship, to go with his five Master's titles and five World Championships (few players have even won one of each of these). His next goal is to accumulate 1000 competitive century breaks before he retires. Although he's nearly 40 and has currently only amassed 750, I wouldn't bet against him achieving this.

For years, the main frustration for the keen snooker fan was the apparently immutable dichotomy between the monotonous winners and the flamboyant losers. It seemed that we could either have the unflappable resolve of a Steve Davis (six-time World Champ) or the charismatic fragility of a Jimmy White (six-time runner-up), but we couldn't have both in one player. By only self-destructing either before the start of a tournament or after winning one, O'Sullivan has cleverly defied this convention. He doesn't fall apart in the crucial stages of a match; he plays consistently throughout, either like the greatest player in the world or only, say, the twelfth best. It all depends on which Ronnie shows up.

The latter stages of a major tournament are when you see snooker at its finest. The Master's will take place later this month, and is contested between the top 16 players in the world. The season concludes in April with the World Championship. I'll be watching.

- Actually, that sounds remarkably like what happened in the first Rocky. But in most Hollywood movies Trump would've won.

Note: this article was originally published on 9th January 2015